Reading the Photograph

It is love that drives me forward into the dark.

I sit down at my extraordinarily messy desk. I spy the edge of an envelope under a stack of papers so high, so disorganized, and so random that they sometimes give up clinging together and cascade to the floor. I wish this were not true. I wish I were the person who keeps a tidy desk. But I am not. And today, seeing the edge of that envelope poking out from beneath the stack of papers somehow liberates my courage and I grasp that poking-out corner and pull the envelope forward. And then I open it.

It contains radioactive material from my childhood. Photographs. Like the letters that I lift, one by one, from the box my niece sent me, the photographs are radioactive. Of course I don’t mean they are dusted with strontium. I mean it’s hard to look at them and it’s hard not to look at them and the terrible ache that accompanies looking at them brings to mind Roland Barthe’s meditations on why and how photographs have this weird power to pierce us. He calls that ability to pierce “the punctum,” the pressure of the unspeakable which wants to be spoken.”

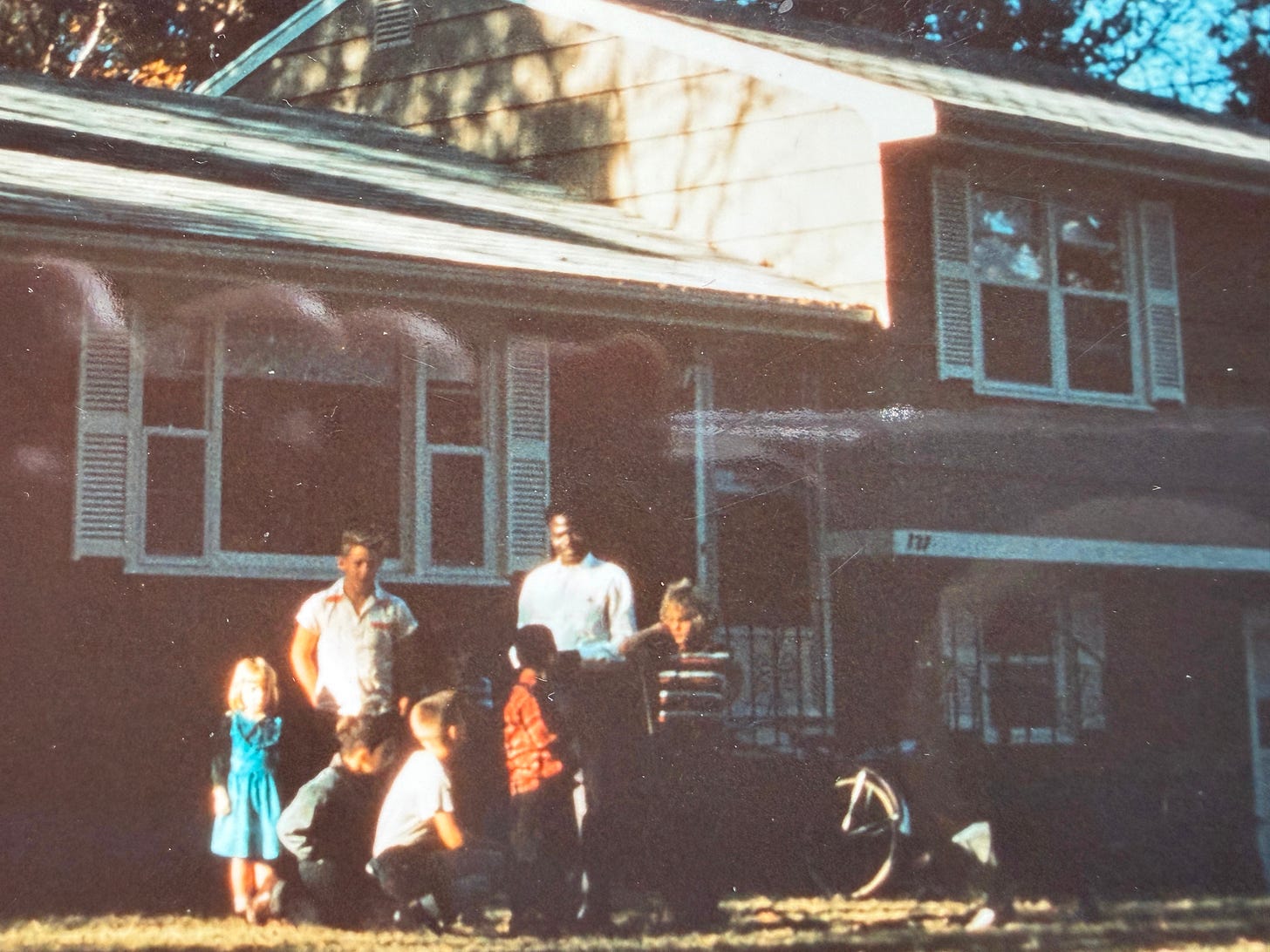

I open the envelope and there I am in my blue jumper, my still-blonde hair making a halo in the sun. The top of my head is level with Joc’s elbow. I can learn a lot from this picture even though the focus is not very sharp and Joc’s face is in shadow. More light! I get my phone flashlight and with it I see Michael kneeling on the grass, and either Patsy or Nan standing, too much in shadow, and maybe a child on a rocking horse, and a tall, dark-skinned man—possibly Asasan, or one of the many dark-skinned visitors Jack brought home from the university. And another boy next to Kunio, a boy I don’t recognize. I am four or five. It’s the South Main house. It must be early fall—there are leaves on the ground and the trees behind the house are autumnal, their leaves russet, and the grass is a color neither wheat nor green, but something in between. Why are we all standing out there in the yard? Who is taking this photograph? If I am 4, Joc is 14. He looks older. He always did look older than his age. I look again and lean more toward 4 than 5. This top-of-head-to-elbow measure makes my memories make sense. Yes, he could have, and did, do exactly as I described above. Plant his hand on the top of my head while I spin and flail and pummel the air in a false fury, so thrilled to have his attention even if it’s teasing. I don’t mind the teasing, not at all. He grins and teases and I am drenched in the love that pours out of his heart, runs down his arm through his hand and into my head and down to MY heart, which hums and glows and chitters and sings. Yes. He did that. And I felt that. And it may be a good place to start this project, this journey, this task of speaking this thing I’ve carried all my life, this big love, this love that runs like a vein of gold right through the heart of my life. What would have become of this big love if he had lived? It would have become ordinary. Just an ordinary girl adoring her ordinary brother. But he didn’t live. He died. At the very moment I was poised on the threshold of becoming a person, standing in the doorway to my life, my balance shifted, one foot hovering in the air on its way to step down into the world. I was seventeen. I’m not at all sure what I knew in the before. Before the great cataclysm of his death. In the after, all was changed. I experienced a blowing apart, an atomization, that, in retrospect, feels fated. As if our destinies were tied in this strange way. The way that twines love and death together like a Celtic knot. Love and death, the only subjects I’ve ever been interested in thinking, talking, writing about. The arrows that drive my seeking and my learning and my understanding still, now, standing upon another threshold at seventy-one, my foot poised to step into the world of old age. It has taken every one of the fifty-four journeys around the sun between the cataclysm and this moment, to begin the unpacking.

Peeling away layers of time and meaning and grieving. You are an artful raconteur. Tell us more.

This is so heartfelt and beautifully written, Rochelle. Thank you for sharing this with us.